First Published in Cycle Canada July 1977

BY JOHN COOPER

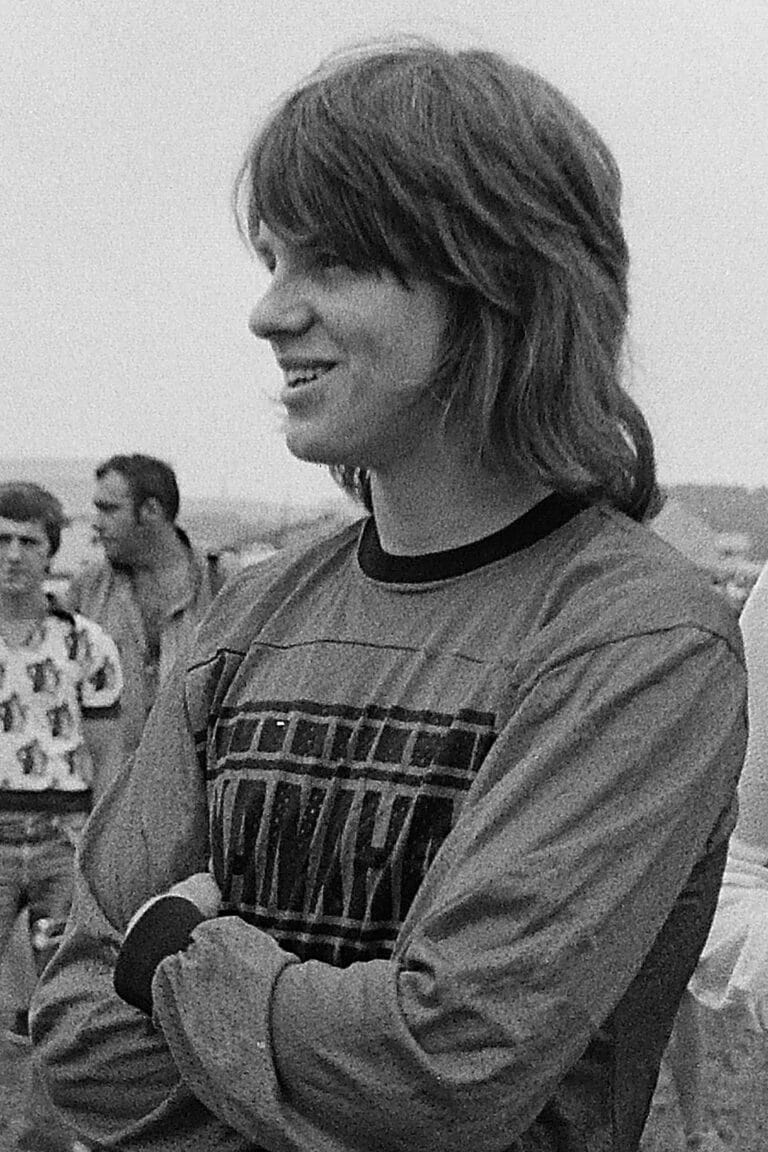

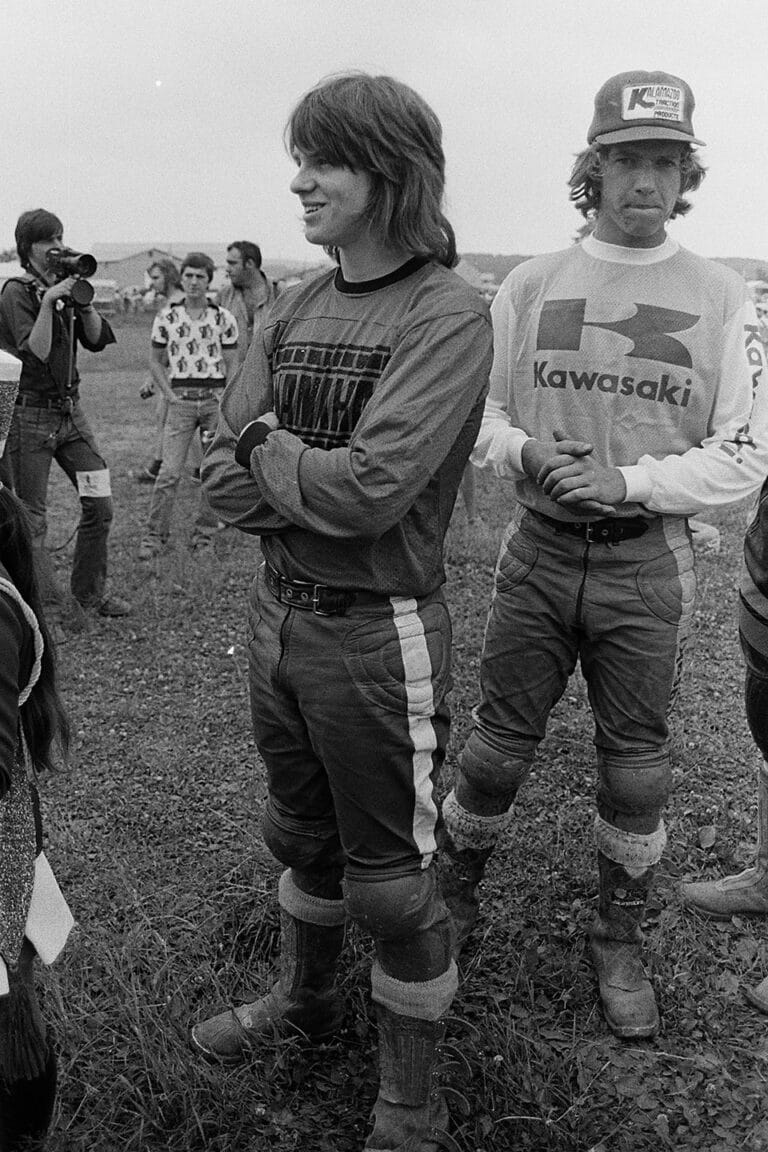

A long, dark scar curves down the inner side of Larry MacKenzie’s right knee, it has 45 stitches and he calls it “the smile. ” It resembles a pair of handlebars, and he jokes about having a cross-brace tattoed on it. But it’s not really funny. This was going to be Larry MacKenzie’s year, but now all bets are off. Will a freak injury at a backwoods track scratch our top native-born rider from the race for No. 1 in Canadian motocross?

The fateful Sunday in March started like many others when MacKenzie made the familiar 3-hour trek from his family home in Burnaby, B. C. To ride against northw-estern U. S. Experts at Puyallup, Wash. It ended when a crash tore the cartilage in his right knee and put him in the hospital just as the B. C. Motocross season was under way.

After the operation which resulted in the scar, he had to spend two months convalescing before he was pronounced fit to ride on a track again.

The 21-year-old who last year was one of Yamaha Motor Canada’s two fully sponsored motocross riders and who won the annual White Memorial Trophy for competition points-gathering will have to prove himself all over again.

His doctor says he’s ready, but the pain persists and MacKenzie knows he will have to take it slow and steady to avoid being hurt again.

He sits on a stool in Yamaha’s near-vacant race shop in Richmond, B. C., discussing his career and and taking a break from preparing a pair of hand-built factory racing machines. The place is quiet at the moment, with only posters on the wall as a reminder of Yamaha’s road racing efforts and Steve Baker’s exploits with the European grand prix circus.

With Bob Work and Baker in Europe, only assistant racing director Ken Molyneux is left at Yamaha’s race team headquarters. MacKenzie is not fully sponsored by Yamaha this year, but is supported to the extent of having two factory bikes to ride.

Slim and confident, yet ‘quiet-spoken, Larry MacKenzie is the second son of a family for whom motorcycle racing is a way of life. His father Dayton retired from AMA professional dirt track competition seven years ago after a 17-year career.Larry’s older brother Glen, 22, was one of the top-ranked motocross riders in Cana da until a car accident in 1973 put him in hospital for months and ended his racing.

Dan MacKenzie, 20, is the youngest. He also is an expert-class motocrosser and rides a Honda in the 125-cc class and a Deeley/Harley-Davidson in the 250 class.

Dayton MacKenzie, who even now is just 42, was top rider in B. C. Dirt track in 1955, 56 and 57. He held the Bellingham, Wash., track record until young Steve Baker came along.

Dayton is an old friend and rival of former sponsor Trevor Deeley, who in more recent years has helped the three MacKenzie boys during their own racing careers.

All three received bikes from Deeley after Dayton finally retired.

Larry says he has never bought any of the motorcycles he raced since starting seven years ago. His first ride was on a 100 Harley in a dirt track event. He tried a 100 Yamaha in the now-defunct Ashcroft corss-country, then switched to motocross and hasn’t ridden dirt track since his first year.

He rode for Clarke-Simpkins on Hondas for two years, and rode a 360 Bultaco for Allied Motorcycles who supplied him with a free machine and parts.

His opportunity to turn professional came two years ago when former No. 1 plate holder Bill McLean broke his leg in an early-season race at Mission. Yamaha asked MacKenzie to ride the national championship series. Ride he did, placing sixth in the 125-cc class and ninth in the open class.

Last year Yamaha offered him full support, including the use of a company race van to travel with Japanese rider Nicky Kinoshita to a full season of races and motocross schools.

This year the big news in Canadian motocross is contingency money and factory-sponsored riders are gone like last week’s hot setup. MacKenzie’s support consists of two exotic, experimental motorcycles, free parts, and the use of Yamaha’s shop facilities.

At hand are the expected benefits of having access to factory machines – a stack of shelves in the corner with bins full of ond of special parts lovingly crafted of exotic metals and complete works engines sealed in plastic bags.

The two bikes, a water-cooled OW-27 125 and a brutal OW-26 400, are special throughout, with aluminum swingarms, titanium bolts here and there, special monoshocks and forks and magnesium sand castings wherever possible.

What those who covet a factory bike don’t see are the endless details which have to be put right before the machine can even go on the track. Hasty diagrams air-mailed from the factory and cryptic messages in Japanese indicate where gussets have to be welded on the frames.

Suspensions have to be tuned, adjusted and modified. Everything is experimental. New parts are rushed through to improve on the old parts which were also produced were in a rush, between the end of one season and the beginning of the next.

Working with these finicky creations on a daily basis you lose sight of the fact that they represent untold thousands of dollars in time, material and engineering talent.

“I expect everyone thinks all I do is ride the bikes, ” he says. “They don’t realize what you have to do to keep a factory bike running.

“And they’re not that easy to ride. It’s probably harder to ride a works bike than a production bike, especially the 250. Ontario rider Allan Logue rides the only OW-25 works 250 presently in Canada. MacKenzie plans to stick to the 125 and open classes.

“It’s not hard to ride three classes here, but I like 30-minute motos. Ride nine of those in a day and you’re dead. “

MacKenzie hopes to keep body and soul together by winning all the Yamaha contingency dollars he can, and cutting expenses by concentrating on local races until the national championship series comes around in September.

He has an equally casual attitude toward the other local experts he will confront practically every Sunday through the summer. “Rick Sheren usually gets the holeshot and then peters out after three laps. Marvel (Marv Cross) goes fast but he usually jumps off. Wally Levy’s good in the open class.

“Dan takes bad lines through corners. I help him pick lines, but he doesn’t train.He’s really skinny, but he’s good on a 125. “Zoli’s good on the Edmonton track, but CZ doesn’t handle that hot.

“When I raced at Edmonton last May, Gaetz was supposed to be winning everything, but I beat him by 30 seconds. But Gaetz is strong and fast and he’s got good style. “

MacKenzie is not too shabby on style himself, but when he’s not being pressed, gen, but he likes to show off for the spectators and the cameras. He’s known for spectacular crossed-up jumps which waste time but impress the crowds.

In general, he’s not impressed by the quality of his local oppostion. “B. C. Stuff, that’s nothing. No. 1 in Canada is what really counts.

MacKenzie’s greatest opponent is his friend Bill McLean, also from Burnaby, who won the No. 1 plate while riding for Yamaha in 1973. McLean now is riding in Europe with fellow westerner Henning Hansen on production Yamahas. He was committed to the trip before MacKenzie’s injury, and so whether he would have been offered factory Yamahas for this year is problematical.

Which of the two riders with the Scottish surnames is the better this year won’t be known until they confront each other in the nationals this fall. McLean will have the benefit of a season in Europe. Mackenzie will have the arguable advantage of works equipment.

Last year MacKenzie was third overall and first native Canadian in the open expert class and the overall standings for No. 1 plate. He was sixth overall in the 250cc class and second Canadian behind Bob Levy.

Whether he can overcome his knee injury, beat McLean, Sallqvist and the eastern hordes and become the first Canadian in No. 1 spot in four years remains to be seen. Some might say he’s had it easy until now.

But when the flag drops, Larry MacKenzie is known for doing the job. This year he intends to win.